Jonathan Heath and Jaime Acosta[1]

Bank of Mexico

INTRODUCTION

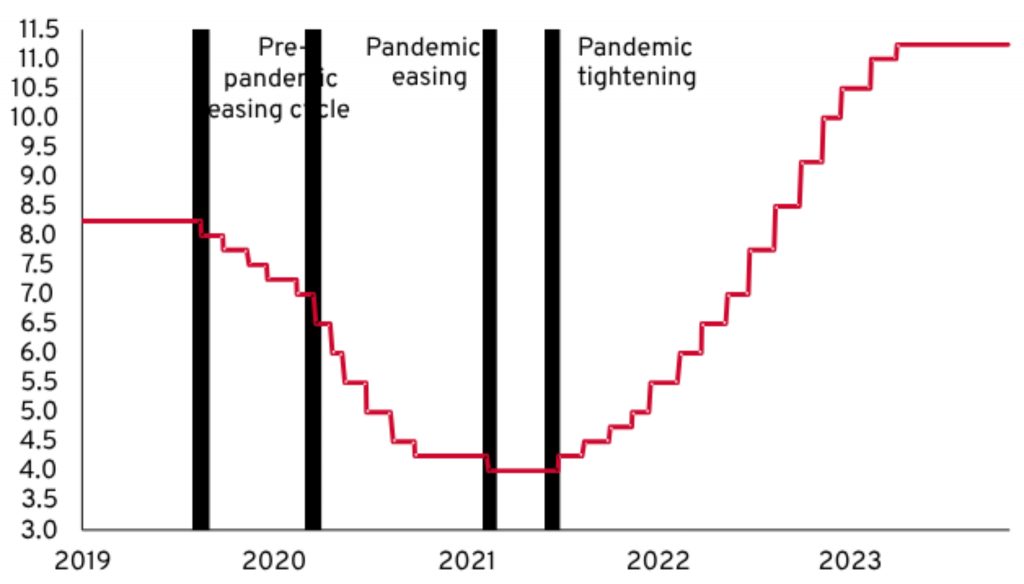

Starting in December 2015, the Bank of Mexico (Banxico) carried out a restrictive monetary policy cycle that saw its target rate reach 8.25% by December 2018.[2] This led Mexico to register an inflation rate of 2.8% (below its target of 3.0%) and the beginning of a mild recession in 2019. As a result, the central bank started an easing cycle in the second half of that year. Beginning in August 2019, the monetary policy rate was reduced

by 25 basis points on five occasions, reaching 7.0% in February 2020. Then the COVID-19 pandemic arrived.

The World Health Organization acknowledged that the COVID-19 outbreak was a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” at the end of January 2020. By the time it was declared a pandemic in March, Banxico was well aware that safe distance and lockdown measures would be causing an economic meltdown and be raising financial stability concerns. As a result, the first stage of ‘pandemic easing’ was implemented, accelerating the pace of the easing cycle up through the beginning of 2021. Likewise, Banxico announced macroprudential measures aimed at improving liquidity, assuring the well-functioning of financial markets, and strengthening credit channels (Bank of Mexico 2020a, 2020b). Since the beginning of the pandemic, monetary authorities were anticipating a greater fall in economic activity compared to other countries in the absence of major fiscal policy impulse.

In a second intermediate stage, uncertain conditions led to a discussion as to whether the pandemic effects on economic activity and inflation were temporary or not. As lockdown measures started to ease, an unforeseen inflationary challenge emerged. Almost at the same time, improved financial conditions and a resilient financial system led to a gradual. phasing out of the complementary and macroprudential measures that, along with a pre-existing strong regulatory framework, had prevented a major deterioration in the Mexican financial system. Finally, a third stage emerged, that could be called the ‘pandemic tightening’. Starting in the second quarter of 2021, economic activity was showing a clear recovery, while mounting global and domestic pressures were causing a rapid increase in inflation could no longer be labelled ‘temporary’. As a result, Banxico began a tightening cycle that evolved into several phases as an exaggeratedly complex inflationary phenomenon unfolded. In this stage, that has not concluded, inflation peaked in September 2022 and finally began to decline. Despite the significant progress, Banxico still faces strong challenges in order to be able see inflation converge toward its 3.0% target and restore normal monetary conditions.

THE ‘PANDEMIC EASING’

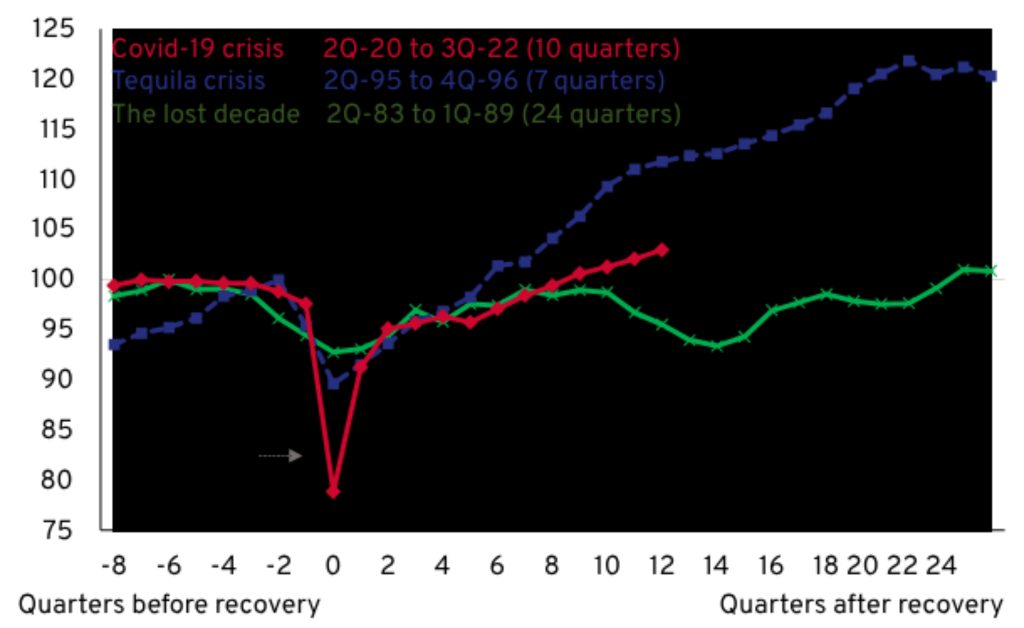

The COVID-19 crisis represented a deep crisis followed by a prolonged recovery. Lockdown policies brought an abrupt GDP fall of 19% in the second quarter of 2020, the largest quarterly decline since the infamous Tequila Crisis. This implied that one out of every three Mexicans looking for a job did not have one.[3] The recovery was not similar to the rapid one observed in the Tequila Crisis in part due to the magnitude of the pandemic shock and the lack of any significant fiscal stimulus (Figure 1). Notwithstanding some marginal fiscal measures announced, the support was far short of the magnitude of the economic backlash.[4] Although this prolonged the recovery process, Mexico avoided the major debt hangover that many countries are suffering in the aftermath of the pandemic. At the time, in the absence of fiscal stimulus, there was limited coordination between fiscal and monetary policies responding to the crisis.

The immediate policy response was an increase in the pace of monetary easing and the announcement of macroprudential policies. The economy was in a mild recession prior to the outbreak COVID-19, while the unprecedented conditions triggered by the pandemic brought about the possibility of long-lasting economic effects and a serious threat to financial stability. For these reasons, Banxico speeded up the easing cycle with five consecutive 50 basis point reductions between March 2020 and August 2020.[5] In September 2020, the central bank adjusted the target rate reduction pace to 25 basis

points and spaced its decreases until it reached the level of 4% in February 2021. Despite cyclical conditions, the Bank’s assessment of uncertainty about the balance of risks for inflation[6] prevented further monetary easing similar to other emerging economies. Likewise, quantitative easing (QE) was never implemented as the zero lower bound was never reached. Indeed, the only asset purchases by the Bank were those introduced with the complementary macroprudential measures listed in the next section.

FIGURE 1 GDP RECOVERY IN THE AFTERMATH OF MEXICAN ECONOMIC CRISES [7]

FIGURE 2 MONETARY POLICY TARGET RATE (ANNUAL RATE, %)

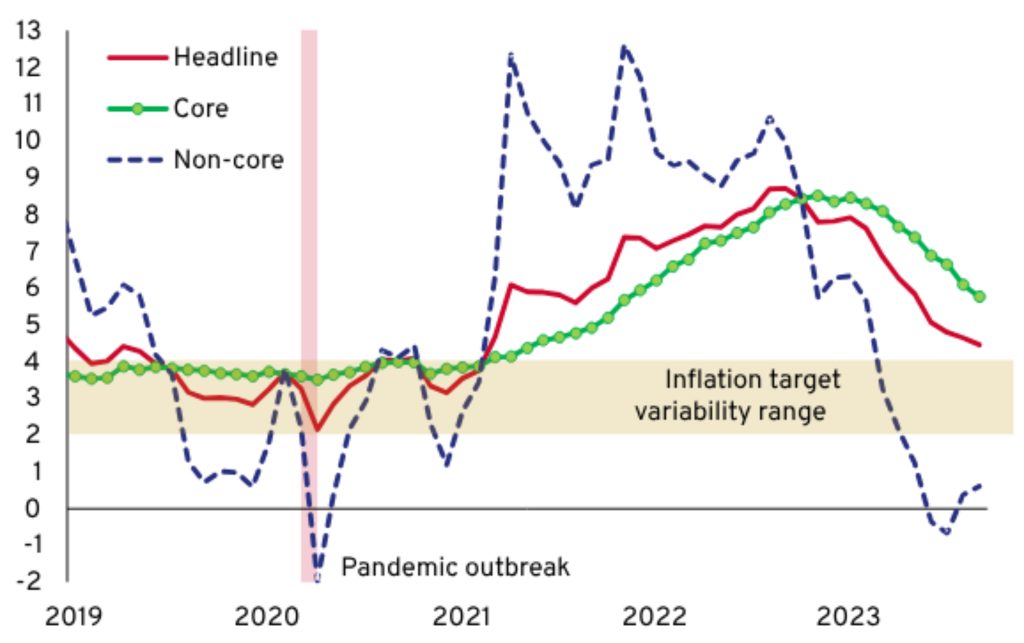

Banxico faced several challenges while easing monetary conditions.[8] First, the pandemic financial distress and economic meltdown demanded quick stimulus that, unfortunately, could not be delivered given the limited effectiveness of monetary policy transmission mechanisms.[9] Second, the lockdown, the sharp loss in household income and the shortage of some products and services led to a new composition of household spending and changes in relative prices. The demand for merchandises increased while demand for many services plummeted. The lockdown also led to negative supply shocks as many products faced restrictions in production resulting in price increases in spite of the huge negative output gap. Nevertheless, declines in prices of services were not strong enough to offset the increase in food prices.[10] Indeed, Mexico’s inflation gap was positive during almost all the pandemic period. Beginning in March 2021, inflation has been above the Bank’s inflation variability target range. Third, the traditional reading of inflation indicators became harder, as CPI fixed weights stopped reflecting changes in household consumption patterns.[11] Fourth, with the likely reduction of potential GDP, the extent of the negative output gap became uncertain.[12] Thus, slackness conditions were less than what models suggested.

FIGURE 3 HEADLINE, CORE AND NON-CORE INFLATION (ANNUAL PERCENTAGE)

COMPLEMENTARY MEASURES AND OTHER MACROPRUDENTIAL POLICIES

Banxico’s complementary measures

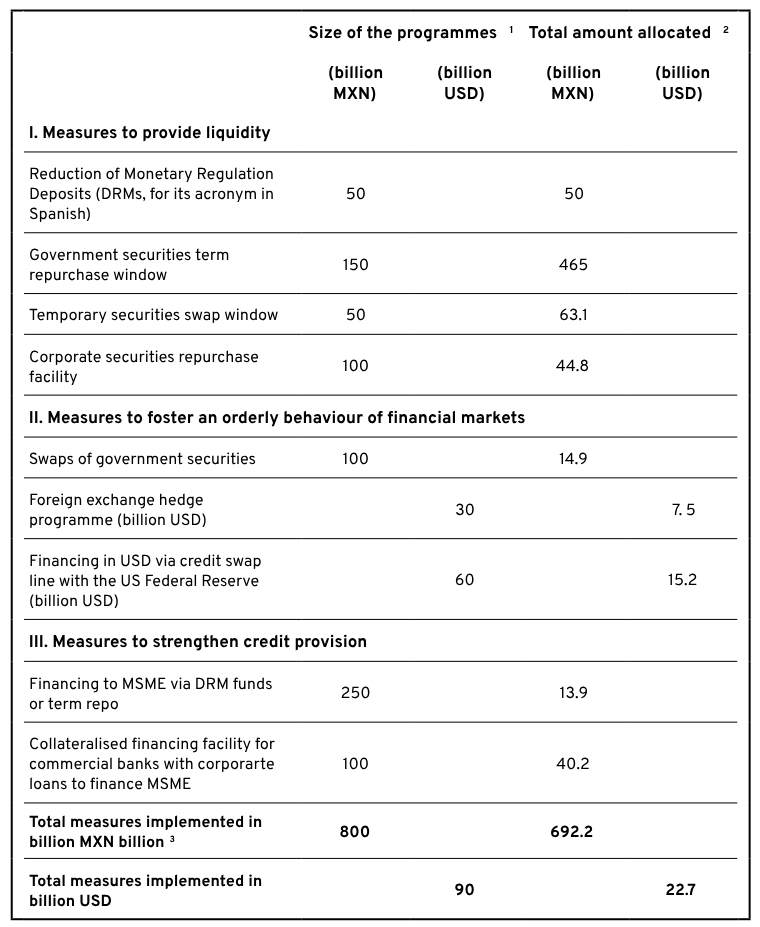

Banxico announced macroprudential measures on both 20 March and 21 April 2020,[13] aimed at increasing liquidity, assuring the well-functioning of the payments system and enticing credit expansion for micro, small and medium-sized firms (MSMEs). The goal was to make sure that financial intermediaries would continue financing economy activity and to ease deteriorating domestic financial conditions. These measures could be classified into three groups, depending on their primary objective, although some could contribute to several objectives simultaneously.[14]

The first group sought to provide adequate liquidity in short-term funding markets and to strengthen commercial banks’ financing to perform their operations under extreme volatility. Banxico allowed a partial reduction of fixed commercial bank deposits in the central bank,[15] reduced the cost of some central bank liquidity facilities,[16] and increased liquidity in the inter-bank repo market during trading hours.[17] Similarly, given the stress in some securities trading, the Bank also opened a government securities term repurchase window,[18] a temporary securities swap window,[19] and a corporate securities repurchase facility.[20] The latter was crucial to reactivate the depressed corporate debt market at the time.

The second group aimed to encourage an orderly behaviour of financial markets and to provide US dollar liquidity. For these goals, the Bank offered swaps of government securities.[21] In collaboration with the Ministry of Finance, some amendments to the Government Debt Market Makers Program were made to foster more participation of the institutions enrolled in this program.[22] Finally, by instruction of the Foreign Exchange Commission, to promote orderly operating conditions in the Mexican peso/ US dollar markets, Banxico granted US dollar financing to credit institutions[23] and a complementary foreign exchange hedge programme to be traded when Mexican markets were closed.[24]

Finally, a third group of measures sought to strengthen credit channels by providing resources to the banking institutions to finance enterprises affected by the pandemic.[25] In addition, the Bank introduced a collateralised financing facility where commercial banks could use their corporate loans as collateral. As the corporate sector used their credit lines, commercial banks had their liquidity reduced. Hence, the goal of this facility was to provide additional resources to the banking sector that could be granted to MSMEs.

From their announcement, these measures sent a strong signal that Banxico was preventing a collapse in the financial system. These measures provided additional support to financial intermediaries that translated into an improvement of the liquidity position, capitalisation levels and availability of funds (Bank of Mexico 2020e). The measures fostered an orderly operation of financial institutions, even for those who did not use the facilities directly. Likewise, they improved the trading conditions of the fixed income and exchange markets, contributing to releasing some financial stress. Regarding the facilities geared towards strengthening credit channels, despite not providing direct lending from Banxico to the non-financial private sector, they gave access to resources that could be used by credit institutions to revert any potential credit crunch.

The Special Accounting Criteria and other macroprudential measures

The Mexican financial system was more resilient at the onset of the pandemic because of the financial reforms implemented since 2008. In Mexico, the development of the current macroprudential policy toolkit has been nourished by international experience and best practices recommended by international organisations, mainly the IMF and the Financial Stability Board (FSB), and the Basel III prudential regulations. In addition to this strength, the regulatory authorities deemed necessary the introduction of temporary macroprudential actions.

TABLE 1 BANXICO’S COMPLEMENTARY MEASURES

Source: Bank of Mexico.

On 29 April, the National Banking and Securities Commission (CNBV) issued a set of Special Accounting Criteria (CCEs from its acronym in Spanish) to relieve potential financial distress. The CCEs allowed the accredited population to defer totally[26] or partially capital and/or interest payments related to onsumer residential mortgage and selected commercial loans.[27] This provided relief to financial institutions’ balance sheets, as balances could be frozen without interest charges. The CCEs were freely adopted by credit institutions[28] and credit activity remained resilient during the lockdown months. Most of the loans related to these CCEs continued to make the scheduled payments that they would have had to make in the absence of said criteria and, therefore, represented a lower risk. In addition, the Mexican authorities provided additional flexibilities embedded in the international regulatory standards.[29] Finally, in Mexico, like in other countries, no capital flow controls were introduced.

The reversal of the complementary and macroprudential measures

The complementary measures in national currency announced by Banxico amounted to 800 billion pesos, equivalent to 3.3% of GDP at the time, and another $90 billion in foreign currency. The total amounst allocated to these measures, including maturities and refinancing, were 692.2 billion pesos and $22.7 billion, respectively (see Table 1 for details). Based on an econometric model, Alba et al. (2023) found that these measures contributed to financial conditions, having a positive effect on the sovereign risk premium, the ten-year government bond yield, the slope of the yield curve, the yield spreads between Mexico and United States, and the exchange rate.

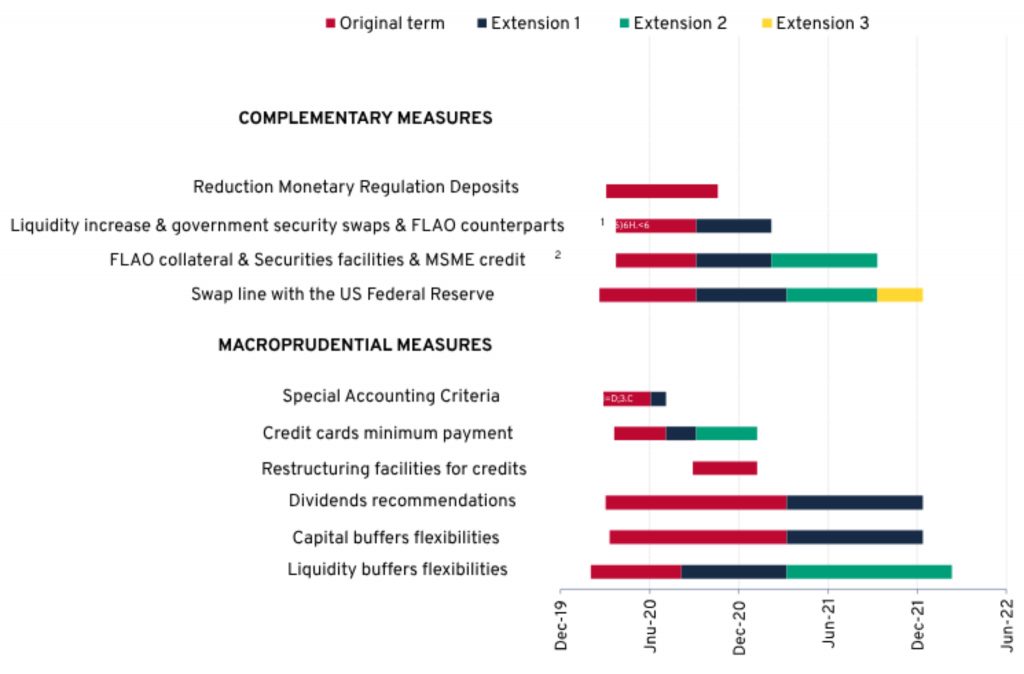

Considering the benefits of these measures and given the risks that persisted in the Mexican economy and financial system, Banxico announced on 15 September 2020 an extension until 28 February 2021. On 25 February 2021, some measures were extended once again till [30] September 2021 (for details, see Figure 4 and Bank of Mexico (2021)). The phasing out of the measures was clearly communicated in advance and at all times the authorities showed willingness to reinstall them or to introduce additional actions if necessary. Likewise, the authorities remained vigilant of potential insolvencies when regulatory relief facilities and financial support were fully unwound. The gradual unwinding avoided abrupt adjustments in financial institutions and did not represent a stress factor for financial stability.

FIGURE 4 TERM OF COMPLEMENTARY MEASURES

Source: Banco de México, Minister of Finance (SHCP), National Banking and Securities Comission (CNBV)

THE ‘PANDEMIC TIGHTENING’ RESPONSE TO THE INFLATION SURGE

The complexity of the pandemic inflation

Even though inflation finished 2020 at 3.15%, the next year started out with a clear upward trend, surpassing 6% by April. The main causes were the mounting global pressures brought about by the pandemic, which disrupted supply chains worldwide and increased the cost of maritime transportation. At the same time, the excessive fiscal and monetary stimulus carried out by many countries contributed to explosive increases in commodities and food prices. The safe distance and stay-at-home policies caused significant shifts in household consumption. The result was increasing inflation in almost all countries. Mexico was not spared, especially because of its global presence in international trade.

Of all price groups worldwide, energy was one of the biggest victims, causing non-core inflation to increase well above core inflation in most countries. In Mexico, however, the government implemented a gasoline subsidy policy aimed at maintaining a quasifixed price. This effort curtailed sharp increases in consumer energy prices, limiting the peak of inflation to 8.7% in September 2022, (below the peak of 9.1% observed in the United States in June of the same year). Without this policy, it is likely that headline inflation would have increased further to a double-digit number, Nevertheless, while this avoided inflation from reaching a higher peak, when gasoline prices started to decrease internationally, it also failed to accelerate the downward trend that many other countries experienced.

In spite of controlling gasoline prices, other energy prices, such as domestic gas, experimented large price swings. This, together with sharp increases in agricultural prices, led non-core inflation to peak at 12.6% in November 2021. Starting in 2022, the non-core component initiated a strong and continuous downward trend, reaching negative annual rates by mid-2023 and becoming the most important factor explaining the decline in headline inflation.

Banxico was very aware that the pandemic inflation was initially sparked by global pressures. As a result, it was clear that for inflation in Mexico to start declining, a necessary (but far from sufficient) condition was that global pressures must start dissipating. Almost all global pressure indicators for inflation did start declining in mid-2022, and by the start of 2023 Mexico saw a shift from global to domestic factors as the main pressure points feeding into inflation. The output gap turned positive, the unemployment gap reached a record negative level and labour costs continued to increase. Merchandise inflation stared to decline, while service inflation (non-tradeables) showed at best a horizontal trend.

Monetary policy tightening

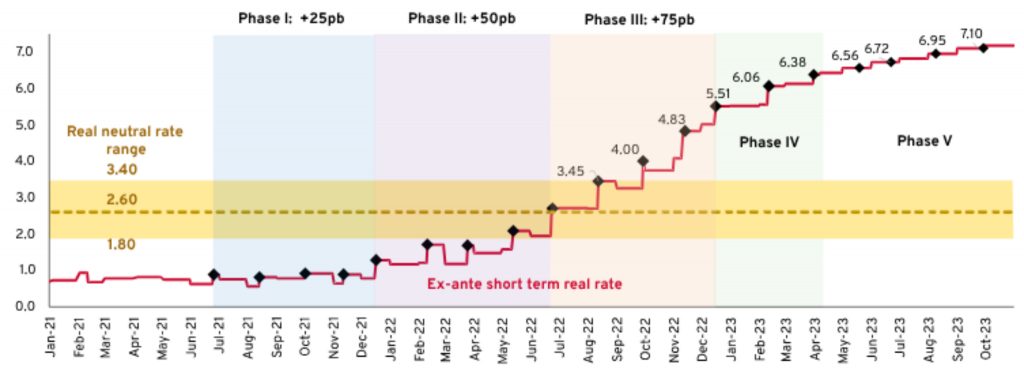

Fortunately, the initial discussion surrounding the transitory characteristic of inflation at the beginning of 2021 was left behind, as the reopening of economic activity, together with mounting global and domestic pressures of prices, called for abandoning the domestic expansionary monetary posture. By the beginning of June 2021, the ex-ante short-term rate of 0.8%30 was well below the estimated neutral rate of 2.6%,[31] implying a monetary posture deep in expansionary territory (Figure 5). As inflation and inflation expectations surged, the Bank needed to start increasing the target rate. Initial discussions were about achieving a neutral monetary stance, anticipating that inflation would soon peak and return back near its target. Nevertheless, it soon became apparent that this inflation episode was much more complex, and needed a much more restrictive stance. For this reason, Banxico started, nine months ahead of the Federal Reserve, a tightening cycle aimed at inflation convergence to its target.

FIGURE 5 EX-ANTE SHORT-TERM REAL RATE (ANNUAL PERCENTAGE)

Source: Bank of Mexico, update: October 2023.

In order to achieve a restrictive posture, the tightening cycle went through three initial phases, with each of them increasing the magnitude of target rate hikes. In the first phase, with the cyclical conditions showing a struggling economy in an uncertain recovery process, the Bank pursued a gradual tightening with four 25 basis point hikes. However, this was not enough to compensate for the deterioration of inflation and its expectations. As a result, by the end of 2021 the ex-ante real rate was practically at the same level as in June, six months earlier. Thus, in December 2021, the restrictive cycle continued with a second phase of four consecutive 50 basis point hikes. During this period, despite increasing the tightening pace, the ex-ante rate barely reached the lower bound of the neutral zone. The monetary stance was still far from being restrictive enough to cope with headline and core annual inflation rates above 7%, more than double the inflation target. As the Mexican economy displayed clear signs of recovery and inflation kept increasing, the restrictive cycle entered a third phase of another four consecutive target rate hikes of 75 basis points, a magnitude of increase never seen before.[32] In October 2022, the real ex-ante rate finally entered into restrictive territory and started approaching a level that was considered appropriate to deal with the complexity of the inflationary environment. Headline inflation, after reaching maximum levels in September 2022, started a gradual reduction, while core inflation peaked in November and initiated a downward trend.

In a fourth phase, in December 2022 the Bank carefully calibrated the terminal rate with a gradual slowdown in the pace of upward adjustments. The terminal interest rate level was attained in March 2023 at 11.25% in nominal terms and near 6.5% in ex-ante real terms. This calibration was important given that, in principle, the nominal target rate would remain fixed for an extended period. During this stage, Banxico balanced between avoiding an early hiking pace deceleration without a significant improvement in the inflationary outlook and reaching a higher-than-necessary terminal rate. The Bank decided to stop hiking considering the monetary policy stance already attained, the lags with which monetary policy operates, the progress in the disinflationary process, the prospects of inflation convergence to the target and the anchoring of inflation expectations.

Thus, starting in May 2023, a fifth phase of the restrictive cycle started with monetary policy management continuing in a passive mode. Although the target rate has remained unchanged at 11.25%, the ex-ante real interest rate has increased 72 basis points through the decline of inflation expectations.[33]In the following months, depending on the convergence of inflation to its target and the resilience of economic activity, the central bank might start a sixth phase with target rate fine-tuning to prevent the monetary policy stance from becoming too restrictive. During this stage, if implemented, the reference rate must begin declining alongside inflation expectations, in order to maintain an exante real interest rate roughly within a range of 7.0% to 7.5%[34] for an extended period of time. Finally, in the last stage, a normalisation towards a neutral monetary policy stance should be adopted, once the inflation target is reached.

Banxico determines its monetary policy decisions through two important postures: an absolute one, defined by its real ex-ante overnight rate of the inter-bank funding market; and a relative posture, demarcated by the interest rate differential between the monetary policy rates of Banxico and the US Federal Reserve. Obviously, the two are linked and cannot be determined separately. However, at times one can be more important than the other. Because Banxico started increasing in June 2021, the monetary policy target rate differential increased from 375 basis points in the first half of 2021 to 575 basis points, nine months prior to the Federal Reserve’s first increase in March 2022. Once it reached 600 basis points after Banxico’s May meeting, the Bank focused on keeping the differential roughly fixed at that level, while trying to attain an appropriate real ex-ante rate. This allowed Banxico to basically ride with the Federal Reserve’s increases up through March 2023, once it decided that it had reached a terminal rate. From that point on, the Federal Reserve’s actions became less relevant, as Banxico’s focus was on maintaining its policy rate at 11.25% for an extended period of time, as explained previously. It is foreseen that in the immediate future, Banxico will not follow the Federal Reserve if the latter decides to increase the Federal Funds rate any further.

After hovering near 20 pesos to the dollar since the beginning of 2021, the exchange rate started to move downwards as of October 2022, falling below 17 pesos by mid-July 2023. While most of this movement could be explained by the dollar depreciation, the peso basically outperformed most other emerging market currencies, with the notable exception of the Colombian peso. The high interest rate differential is pointed out by most as being one of the most important factors. Nevertheless, non-residential holdings of Mexican public-debt bonds showed significant outflows throughout the time that the peso was appreciating.

Important studies carried out by Banxico have all concluded that Mexico’s passthrough coefficient is very low.[35] Nonetheless, the significant appreciation has definitely contributed to lower global pressures throughout the last year. The strength of the peso not only has helped offset higher international prices, but has also contributed to preventing inflation expectations from increasing too much.

The major risks going forward

Headline inflation is expected to finish 2023 somewhere near 4.5%, with core edging towards 5.0%. Given that inflation is approaching the upper limit of the +/-1% variability range around its 3.0% target, many have called for the beginning of a downward cycle in the reference rate as soon as possible. The Bank of Mexico, however, is likely to proceed with caution and prudence as the balance of risks for inflation remains with a clear upward bias. Most of these risks come from a very resilient economy with a very tight labour market, and an expected fiscal boost in the first half of the year. All indicators of slack, including the output gap, are consistent with demand-side pressures. In particular, the prices of services are expected to keep increasing, given its cyclical behaviour. The favourable base comparison that was observed in 2023 is expected to revert, as well as the downward trend in non-core inflation. These risks point to a high degree of persistence, especially in core inflation.

The Bank’s current forecast sees headline inflation finishing around 3.3% in 2024 and finally converging to its 3.0% target by the second quarter of 2025. This last push, however, will be more difficult than that achieved in the previous year, which definitely calls for maintaining a restrictive stance for an extended period, beyond 2024.

Banxico’s communication during the restrictive cycle

During the first phase of the restrictive cycle, the use of forward guidance was limited. Indeed, from June 2021 until November 2021 the Bank stated in its monetary policy press releases the assessment that the inflationary shocks were largely transitory. Nevertheless, the horizon over which they could have an effect was unknown. This assessment was removed in December 2021, once the restrictive cycle reached its second phase of 50 basis

point hikes.

As the restrictive cycle advanced, forward guidance became key for managing market expectations. Since May 2022, specific words have been used in forward guidance to signal more aggressive hikes,[36] more data dependency,[37] or revisions in the rate of an increase of the target rate.[38] This wording has been effective since most market specialists have successfully anticipated the target rate movements. It is important to emphasise that these references do not represent an unchanged commitment by the central bank, since all decisions are subject to the information available and could be modified if something unforeseen occurs.[39] For now, the central bank’s current forward guidance should keep signalling that the policy rate will remain fixed for an extended period[40] with a restrictive stance that will not yield until the primary mandate is fulfilled. As recently documented (Heath and Acosta 2023), Banxico should keep pursuing more clarity, better communication and more transparency in the conduct of monetary policy.

Given the current inflation forecast targeting framework, central bank credibility is essential for efficient monetary policy transmission. For this reason, the Governing Board aims at consistent policy action with the primary goal of low inflation all the time. Credibility is crucial to keeping inflation expectations anchored, despite some deterioration during this inflationary episode. The Bank still faces some challenges, such as consolidating short-term inflation expectations within the target range and achieving long-term expectations, centred at least around the same pre-pandemic levels. Likewise, it is imperative that our expected inflation trajectory stops being subject to major revisions in order to minimise any potential reputational cost.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The COVID-19 crisis represented unprecedented complications. Throughout all the stages of the policy response, Banxico has set a key policy rate that is deemed consistent with inflation convergence. The policy decisions have been introduced in a timely manner, looking for an anticipation of the effect of the multiple shocks faced. The Bank has been using additional communication tools to manage market expectations. Likewise, the pursuit of additional mandates, such as promoting the sound development of the financial system and fostering the proper functioning of payment systems, has

been addressed by complementary macroprudential measures. It is worth mentioning that the COVID-19 crisis did not have a significant effect on the stability of the financial system, due to the existing regulatory framework.

Although Banxico’s priority mandate is price stability, monetary policy decisions have also considered cyclical positioning, particularly in the absence of expansionary fiscal policy and the uncertainty around the long-term effect on potential output. As the Mexican economy goes through a long recovery process, Banxico will exploit all the degrees of freedom that its primary mandate grants in order to successfully complete the normalisation process.

On a final note, it should be understood that monetary policy transmission in Mexico is less effective than in other countries, not only in comparison to developed economies but also compared with emerging countries that are considered peers. This is due mainly to the low levels of financial depth and inclusion, low credit penetration, the high levels of informality, and the lack of competition in the financial system. Many sectors of the economy with limited competition have seen firms with market power continuing to increase their prices, despite the fact that the supply shocks that drove the increases have dissipated. All said, these factors have slowed down the decline in inflation and increased the need for a longer period of monetary restriction.

REFERENCES

Alba, C, G Cuadra and R Ibarra (2023), “The effects of central bank extraordinary measures on financial conditions: Evidence from Mexico”, Applied Economics.

Arshad M U, Z Ahmed, A Ramzan, M N Shabbir, Z Bashir and F N Khan (2021), “Financial inclusion and monetary policy effectiveness: A sustainable development approach of developed and under-developed countries”, PLoS ONE 16(12): e0261337.

Bank of Mexico (2012), Quarterly Inflation Report, July–September 2012.

Bank of Mexico (2017), Quarterly Inflation Report, April–June 2017.

Bank of Mexico (2019), Quarterly Inflation Report, April–June 2019.

Bank of Mexico (2020a), “Measures to provide MXN and USD liquidity and to improve the functioning of domestic markets”, 20 March.

Bank of Mexico (2020b), “Additional measures to foster an orderly functioning of financial markets, strengthen the credit channels and provide liquidity for the sound development of the financial system”, 21 April.

Bank of Mexico (2020c), Quarterly Inflation Report, January–March 2020.

Bank of Mexico (2020d), Financial Stability Report, June 2020.

Bank of Mexico (2020e), Quarterly Inflation Report, July–September.

Bank of Mexico (2020f), Quarterly Inflation Report, October–December 2020.

Bank of Mexico (2021), “Modificación de la vigencia de las medidas orientadas a promover un comportamiento ordenado de los mercados financieros, fortalecer los canales de otorgamiento de crédito y proveer liquidez para el sano desarrollo del sistema financiero”, 25 February.

Heath, J (2021), “Los indicadores en tiempos de pandemia”, in Lecturas en lo que indican los indicadores. Cómo utilizar la información estadística para entender la realidad económica de México, Vol. 3, Museo Interactivo de Economía (MIDE).

Heath, J and J Acosta (2023), “Claridad y transparencia en la comunicación de la política monetaria”, Revista de Economía Mexicana, Anuario UNAM 8.

Jungo, J, M Madaleno and A Botelho (2022), “The Relationship between Financial Inclusion and Monetary Policy: A Comparative Study of Countries’ in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean”, Journal of African Business 23(3): 794-815.

Reinsdorf, M (2020), “COVID-19 and the CPI: Is Inflation Underestimated?”, IMF Working Paper No. 2020/224.

Tapia, E, J Ávalos, G Ahuactzin and I Cortés (2022). “Confined Consumers and Inflation in Times of Covid-19: The Case of Mexico”, in Impactos del COVID-19 en la Economía Mexicana: Estudios de índole social y económico, Lectorum and Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Jonathan Heath is Deputy Governor of Mexico’s central bank (Banxico). Prior to joining the Bank, he was Chief Economist for Mexico for various global financial institutions and international consulting firms. He has lectured on the Mexican economy at five major universities in Mexico, has written numerous articles that have appeared in more than 60 magazines and newspapers, both in Mexico and abroad, and has given conferences on the Mexican economy in more than twenty countries. The titles of books that he has authored are Understanding the Bank of Mexico, Mexico and the Sexenio Curse, Money and What Economic Indicators Indicate.

Since 2019, Jaime Acosta is an advisor to the Board of Governors of the Bank of Mexico on issues related to monetary policy and central banking. Previously, he was a researcher in the Central Banking Operations Directorate at the same institution. During his career he has carried out multiple analytical works related to monetary and exchange rate policy. Mr. Acosta holds a MS in Statistics and a PhD in Economics from Rice University.

[1] The authors thank Alejandra Muciño and Edwin Tapia for providing excellent research assistance. Likewise, we are grateful to the Bank of Mexico’s Financial Stability Department staff Jorge García, Alejandro Saucedo, Jorge Guerrero and Lorenzo Bernal for their comments and insightful data that made some of the graphic material possible.

[2]Factors that motivated this cycle were the Fed’s restrictive cycle, uncertainty derived from the Trump administration, a pronounced Mexican peso depreciation and, later on, an abrupt increase in gasoline prices in 2017. Similarly, events like the Mexican presidential election in 2018 and the cancelation of Mexico City’s new airport contributed to the uncertain environment.

[3] The extended unemployment rate, equivalent to the U-4 definition used by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, surged above 30%.

[4] These measures amounted 242 billion pesos, approximately 1% of GDP at the time of the announcement. For a detailed description, see Bank of Mexico (2020c).

[5] The March monetary policy decision was moved forward from 26 March to 20 March, while the April 2020 decision was made in an unscheduled announcement.

[6] From June 2019 to February 2021, in the monetary policy statements the balance of risks for the expected inflation trajectory was deemed as uncertain.

[7]The GDP peak prior to each recession equals to 100. The zero-time lag represents the period where the GDP reached it minimum point. The shaded area represents the period when GDP reached its pre-recession level.

[8] Banxico does not have a dual mandate like the US Federal Reserve; the priority mandate is price stability. Under the current inflation targeting framework, this means inflation centred at 3%, within a variability range of +/- 1%.

[9] Monetary policy is less effective compared to major advanced and other emerging economies due to much lower financial inclusion, financial deepening, credit penetration, and a very high level of informality and banking system concentration. For some empirical evidence, see Jungo et al. (2022) and Arshad et al. (2021).

[10] For more details see Bank of Mexico (2020f).

[11] Compared to other countries, Mexico has higher CPI weights for food merchandise and lower weights for services; thus, changes in relative prices were amplified in headline inflation. In addition, given the changes in consumption patterns, traditional CPI weights were under-reporting true inflation for households’ consumption basket at the time. For more details about challenges in CPI interpretation due to change in consumption patterns, see Reinsdorf (2020) and Tapia et al. (2022).

[12] For a more comprehensive discussion, see Heath (2021).

[13] The press releases are available on Bank of Mexico (2020a, 2020b).

[14] A summary of these measures was published in Bank of Mexico (2020c).

[15] This involved a 50 billion pesos reduction out of 320 billion pesos in Monetary Regulation Deposits that were held on a permanent basis by commercial and development banks in the central bank.

[16] The interest rate of the credits and repos made through the Ordinary Additional Liquidity Facility (FLAO, for its acronym in Spanish) was lowered from 2.0–2.2 to 1.1 times Banxico’s target for the overnight interbank interest rate. Also, there was an increase of titles eligible for the FLAO collateral.

[17] With this measure the bank maintained a daily level of excess liquidity during financial markets’ trading hours.

[18] In this window, the repurchase at longer terms than those of regular open market operations was allowed.

[19] Aimed to specific illiquid instruments.

[20] This provided liquidity to corporate securities.

[21] In these swaps, Banxico received long-term securities (ten years and longer) and delivered others with maturities of up to three years as long-term securities trading conditions had deteriorated.

[22] For more details, see the press release of 20 March mentioned previously.

[23] Using the temporary US dollar liquidity arrangement, the “swap line” with the US Federal Reserve, Banxico conducted US dollar auctions to increase the availability of dollar financing for private sector participants. This measure provided certainty of funding for the entire financial system and their mere announcement had calming effects.

[24] These hedge transactions were settled by differences in US dollars.

[25] This funding had to be channeled to MSMEs and individuals and could be guaranteed using DRM or some eligible securities.

[26] The deferral was for up to four months with the possibility of a two-month extension.

[27] As long as the credit accounting was classified as current as of 28 February 2020 and the implementation was carried out within 120 calendar days following this date. Later, the CNBV allowed the inclusion of credits that were valid until 31 March.

[28] Initially, the validity of the period of adhesion to the CCE concluded on 26 June 2020. However, the CNBV decided an extension until 31 July 2020.

[29] For more details, see Bank of Mexico (2020d).

[30] The short-term ex-ante real rate is constructed using the target for the overnight interbank interest rate and 12-month inflation expectations from Bank of Mexico’s Survey. At the time, the monetary policy target rate was 4% and 12-month inflation expectations were at 3.2%.

[31] The neutral rate is estimated to be a middle point of 2.6% in a range of different estimations. For more detail, see Bank of Mexico (2019).

[32] The current monetary policy regime that uses an objective for the interbank overnight funding market started in 2008. Data prior to this point in time are not comparable.

[33] With data up through the end of October 2023.

[34] This range is a result of our own estimations and does not necessarily coincide with the Bank staff’s.

[35] For further details see Bank of Mexico (2012, 2017).

[36] In May 2022, to suggest an increase of the hiking pace from 50 basis points to 75 basis points, in the press release it was stated that “taking more forceful measures may be considered”. The wording “same forceful measures” was also used to refer to the 75 basis point hike in June 2022.

[37] For example, in the monetary policy announcements of August, September and November 2022.

[38] In December 2022, the forward guidance stated that the increases would continue, but the pace of the increase would be assessed and adjusted..

[39] In February 2023, the Governing Board faced an upward surprise in inflation that prevented an anticipated reduction of the rate increase pace by some analysts.

[40] Since May 2023, the forward guidance has signalled that “it will be necessary to maintain the reference rate at its current level (11.25%) for an extended period”.